Dec 10, 2020 | The Latest News

The 2020 Champions of the Earth are part of a legacy of people whose effective action led to the environmental victories that have transformed our societies for the better. By showcasing news of the significant work being done on the environmental frontlines, the Champions of the Earth Awards aim to inspire and motivate more people to act for nature. Dr. Robert Bullard is the recipient of the 2020 Champions of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award. Click here to view Dr. Bullard’s profile page.

Read more

Dec 8, 2020 | The Latest News

The Trump administration on Monday rejected setting tougher standards on soot, the nation’s most widespread deadly air pollutant, saying the existing regulations remain sufficient even though some public health experts and environmental justice organizations had pleaded for stricter limits.

The Environmental Protection Agency retained the current thresholds for fine-particle pollution for another five years, despite mounting evidence linking air pollution to lethal outcomes in respiratory illnesses, including covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Documents obtained by The Washington Post show that the EPA has disregarded concerns raised by some administration officials that several of its air policy rollbacks would disproportionately affect minority and low-income communities.

Read more

Dec 3, 2020 | The Latest News

Africatown on “60 Minutes”

On Sunday, November 29th CBS “60 Minutes,” featured one of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice’s partner communities — Africatown, a historic Black community in Mobile, Alabama.

Click here to view Africatown “60 Minutes” Report.

Read below about the HBCU-CBO Gulf Equity Consortium’s work for environmental justice in Africatown

Unique consortium fights for the future of Africatown

Africatown, an historic Black community in Mobile, Alabama, is gaining national and international attention following the discovery of the Clotilda schooner on May 22, 2019. The Clotilda is the last known slave ship in America. One hundred and ten Africans kidnapped from their homeland in present-day Benin were forced on board the Clotilda for enslavement in Mobile, Alabama. The year was 1860 – the year before the start of the Civil War. What the people did with their newly found freedom at the end of the war was remarkable. From different areas, they came together and established their own community that they named Africatown. The homes, churches, and the Mobile County Training School are all a testament to the shared purpose of the founding families to establish Africatown as a residential community for themselves and future generations.

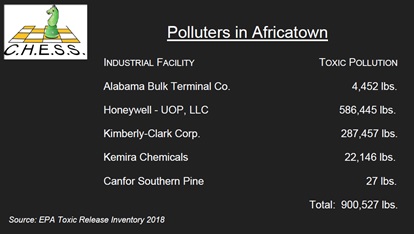

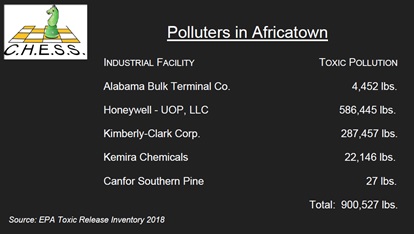

The vision and sacrifices of Africatown’s founding families are under assault by industrial corporations. Two of the five largest industrial polluters in Mobile County are clustered next to Africatown. Land and water contamination as well as air pollution threaten the health and wellness of Africatown residents. The pollution also contributes to climate change that has severe impacts on the Gulf Coast area where Africatown is located.

“The future of Africatown requires us to fight for environmental justice. That’s why we joined the HBCU-CBO Gulf Coast Equity Consortium,” said Major Joe Womack (USMC-retired). Major Womack founded CHESS Community to preserve the history and sustain the future of Africatown. CHESS, which stands for Clean, Healthy, Educated, Safe and Sustainable, works to protect Africatown against industrial expansion. The organization also works to restore natural surroundings and nearby waterways that children and adults in Africatown can enjoy.

The Consortium works regionally in the five Gulf Coast states to improve the lives of children and families in Black communities harmed by pollution and vulnerable to climate change. In the Consortium, community-based organizations partner with professors at six HBCUs for long-term collaborative research and action to achieve environmental justice and equitable climate solutions. The Consortium is co-directed by noted advocates and scholars Dr. Beverly Wright, Executive Director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, and Dr. Robert Bullard, Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University.

“In Africatown and across the Gulf Region, we see historic African American communities used as dumping grounds for toxic industrial facilities and denied the assistance they need for hurricane and disaster recovery. The severe health problems from toxic exposure, which are worsened by COVID-19, and the inequitable climate risks suffered by Black communities are all rooted in systemic environmental racism. We have designed the Consortium to build a grassroots infrastructure that supports communities to lead the research for solutions and strategic actions for achieving them,” said Dr. Wright.

Nov 6, 2020 | The Latest News

Over 48,000 people have died of the novel coronavirus in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas — the five states that make up the Gulf Coast. That’s 20% of the over 234,000 people who’ve died across the country. In all of those states, Black people have had either the highest or second-highest coronavirus death rate in these states, according to APM Research Lab

Read more

Oct 28, 2020 | The Latest News

Dr. Robert Bullard had trouble selling a book in the late Eighties about what he knew to be true. He had written about a subject on which he’d long sounded the alarm: racism involving a sort of discrimination that is much more silent, a violence that doesn’t come via a policeman’s gun or baton. It doesn’t carry the dramatics of a cross burning on the lawn, nor make as many headlines as the racial disparities in America’s economic or medical systems. Bullard was trying to tell the world about the kind of racism that could come through our water taps, or just be floating in the very air that we breathe.

Read more

Oct 14, 2020 | The Latest News

How racism fuels COVID-19 deaths in Cancer Alley.

African Americans living in Cancer Alley suffer from high rates of cancer. The Deep South Center for Environmental Justice is featured in the six-part series as USA Today investigates how racism fuels COVID-19 deaths.

Read more.